These special keyboards, with narrow key sizes, are making it easier for those with smaller (or say normal) hands to enjoy playing the piano; though some still wonder why a lot of manufacturers are still not doing the same.

- 18th-century composer and organist, the great Johann Sebastian Bach had exceptionally large hands. While most of us can just about reach an octave on a piano, which is a span of eight white keys, Bach’s hands could span twelve white keys (almost fifty percent more), as mentioned in this report.

- Elton John gave up classical music because his hands were smaller, unlike that of Sergei Rachmaninoff who was six-feet-six-inches tall

- Many musicians love jazz but struggle to play a tenth or an eleventh chord on the piano.

- Same goes for a lot of women as well, who generally have smaller hands.

Musicians with small hands love the Special keyboards at SMU (Southern Methodist University), Dallas (Texas). These smaller/alternative keyboards make it possible for pianists of every hand size to achieve their artistic potential.

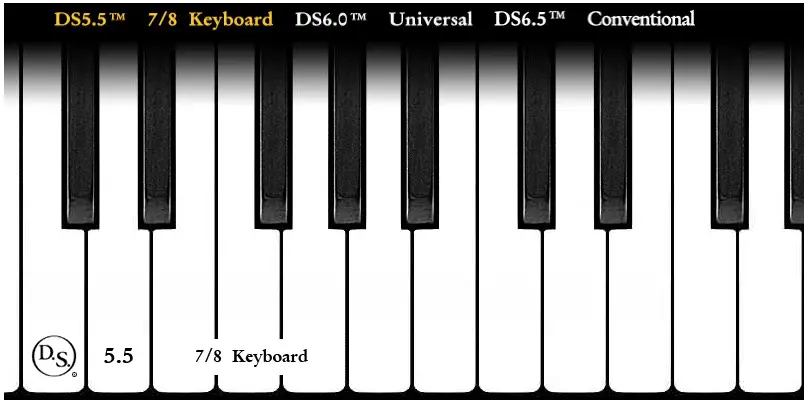

The piano program run by Meadows School of the Arts (within SMU) uses alternate grand piano actions for students with smaller hands. The alternate grand piano actions come in 6 inches and 5 1/2 inch octave width, compared to the 6 1/2 inches of a regular grand piano. The alternate action, which can be replaced in the program’s pianos, helps keep pianists (with smaller hands) healthy and expands what the student is already able to play.

For a long time, piano players with smaller hands had no option but to somehow figure out how to play the octave notes (despite their fingers not wide enough) or skip certain compositions (of Romantic-era composers including Beethoven and Brahms). There are some more determined players who got themselves injured by spending hours trying to play ‘stretchy’ passages.

Thanks to the efforts of SMU keyboard studies chair Carol Leone, the school became the first major university in the U.S. to incorporate smaller keyboards into its music program, leveling the playing field for many piano students with smaller hands.

The first time Eliana Yi (undergraduate student in piano performance) tried one of the smaller keyboards, “I remember being really excited, because my hands could actually reach and play all the right notes. Ever since, I haven’t had a single injury, and I can practice as long as I want.”

For decades, not many questioned the size of the conventional piano. If someone’s thumb-to-pinky reach was less than 8.5 inches (the distance considered ideal to comfortably play an octave) s/he just didn’t have any other option. And those caught shorthanded are mostly women, with spans an inch shorter than men, on average.

For such players, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to properly play many works of Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt and Brahms; the works of Rachmaninoff are particularly daunting.

Those who attempt “stretchy” passages either omit certain notes, avoid certain compositions or risk tendon injury with repeated play.

One such player, read an article in Piano and Keyboard magazine about the smaller keyboards, and the discovery completely changed her life and career.

In addition to reducing injury caused by overextended fingers, the players could now play classic compositions that required larger-hands. The smaller keyboards have instilled new confidence in players with smaller hands. It’s not their own limitations that have held them back, they realize; it’s the limitations of the instruments themselves. Once limited to baroque and early classical works, students are now able to play the type of repertoire by which pianists are typically judged (at competitions).

These smaller keyboards are also called “alternatively sized” or “ergonomically scaled” keyboards. Pennsylvania-based Steinbuhler & Co. produce the smaller keyboards used at SMU.

Carol Leone occasionally visits other schools with a retrofitted piano to demonstrate the simple process of switching out keyboards, trying to convince them to follow suit. She has also written a number of articles in magazines such as American Music Teacher and Piano Professional.

SMU has several pianos retrofitted to accommodate the smaller-sized keyboards for practice, lessons and performance; the university also hosts the Dallas International Piano Competition along with the Dallas Chamber Symphony, that allows pianists to play any-sized keyboard.

Meanwhile, a group called Pianists for Alternatively Sized Keyboards aims to convince major piano manufacturers to make variably sized keyboards as well.

The notion of smaller keyboards first met resistance from some traditionalists, although its gradually fading. “There are some very traditional people who believe there should be one standard. They’re people who think of piano as a competitive thing — like it’s a basketball hoop. But this is art, it’s not sport. It’s about making as much beautiful art as possible, and we should give everybody the opportunity to do that,” says Carol Leone.

Information from: The Dallas Morning News, http://www.dallasnews.com

Read: Best digital pianos for beginners

KeytarHQ editorial team includes musicians who write and review products for pianists, keyboardists, guitarists & other musicians. KeytarHQ is the best online resource for information on keyboards, pianos, synths, keytars, guitars and music gear for musicians of all abilities, ages and interests.

Leave a Reply